(This is an edited version of a post first published on April 21, 2012)

In India, cinema isn’t just a passion. It is an obsession. We have perhaps inherited this acute addiction from the man who started it all, 100 years ago – the Father of Indian Cinema Dhundiraj Govind Phalke (1870-1944). Dadasaheb Phalke as we now better know him as, held the first show of Raja Harishchandra what is widely considered to be the first Indian feature film at Bombay’s Olympia Picture Palace on April 21, 1913. The commercial screenings started 12 days later, on May 3, 1913 at Coronation Cinematograph and Variety Hall, Sandhurst Road, Girgaum, Bombay.

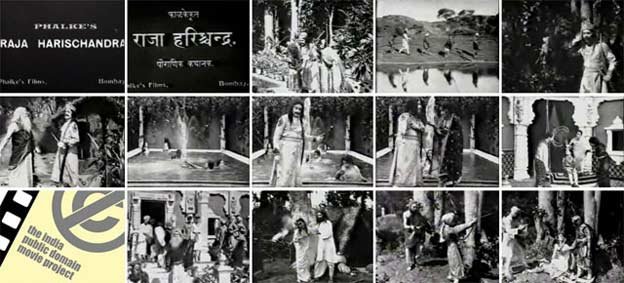

Most of us have seen only fleeting glimpses of this bud, that gradually grew to the mammoth movie industry that we have in India today. The actual film title spelt the name of the film as Raja Harischandra, minus an h.

Since Phalke made the best of the technology available to him at his time, I thought it would be a tribute to the innovator in him to convert the film in 3D. Using YouTube’s 3D conversion technology you can also watch Raja Harishchandra in 3D. In the video embedded below, click on the settings (gear) icon and the 3D link will appear from there choose greyscale and also the type of 3D glasses you own to watch how India’s first feature looks in a 3D avatar (Don’t expect an Avatar though).

Here are 11 minutes and 19 seconds of what is left of the landmark film (India’s film archival history isn’t something that we can be very proud of).

This movie has been posted both on YouTube as well as the Internet Archive as part of the India Public Domain Movie Project.

[Download Raja Harishchandra (1913) AVI 192.2 MB | MP4 56.3 MB | OGG 41.6 MB]

What you see above is apparently only the first reel of the movie. This video has been extracted and edited from a 1967 documentary DG Phalke, The First Indian Film Director 1870-1944 produced by the Indian National Film Archive.

There is some confusion on whether this film, preserved in the National Film Archives of India, is the actual 1913 film or a 1917 remake of the film.

Raja Harishchandra. A performance with 57,000 photographs. A picture two miles long. All for only three annas.

This is how Phalke, Indian cinema’s first marketing wizard promoted his creation. Phalke had to make his soundless cinema with higher ticket prices appeal to an audience who were hooked to stage plays, then the reigning form of entertainment.

Raja Harishchandra wasn’t the first Indian film, but it was the first indigenously produced feature length film and Phalke’s story of making the film is as interesting as a movie plot. Harishchandrachi Factory, the 2009 Marathi film on Dadasaheb Phalke that centres on the making of the movie is a must watch. Had the film not been a biopic, it could have also passed as a well-made subtle comedy. This UTV produced Paresh Mokashi directed movie was also India’s official nomination to the Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. If you haven’t yet watched it, my suggestion is that you see Raja Harishchandra before you sit down to watch Harishchandrachi Factory. When you see the same scenes recreated almost a century later on a film canvas that’s much wider, the impact is that much greater (Harishchandrachi Factory, along with Raja Harishchandra was chosen as one of the top 100 films of Indian cinema by IBNLive.com)

Phalke is often compared to the French film pioneer Georges Melies, both considered the medium as an art form and also had expertise in magic tricks and that knowledge they made use of for special effects in their films.

Raja Harishchandra. A powerfully instructive subject from the Indian mythology. First film of Indian manufacture. Specially prepared at enormous cost. Original scenes from the sacred city of Benaras. Sure to appeal all Hindu patrons (from a pamphlet promoting the film)

The entire show, apart from the movie included other forms of non-film entertainment as well. Raja Harishchandra was also exhibited in London in 1914.

The story for the movie was from the great epic Mahabharata and espouses the belief that truth always triumphs. Harishchandra was a legendary pious king of Ayodhya who sacrificed his kingdom, wife and child for the sake of truth. Harishchandrachi Factory tells us that this story was a favourite with Phalke’s sons and his eldest son Bhalachandra Phalke also played Rohitashwa, Harishchandra’s son in the movie. Another important reason why this story was chosen for the film was that Harishchandra was a popular theme in the Marathi and Urdu theatre of the day. The story again found itself in another first-of-its-kind movie, the first Marathi talkie, V Shantaram’s Ayodhyecha Raja (1932), which was also released in Hindi, making it the first Indian film to be released in two languages.

Raja Harishchandra was shot in a bunglow (apart from other outdoor locations) called Mathura Bhawan (owned by one Mathuradas Makanji) located on a street in Dadar, Bombay that is now rightly named Dada Saheb Phalke Road.

The acting was in traditional Indian folk theatre style, the influence of which and Parsi Theatre were to remain on Indian acting for decades. In the absence of sound (that was to make an appearance in Indian cinema 18 years later with Alam Ara), there were title inserts between shots explaining the plot. In Raja Harishchandra (and most of the films of the silent era) these title plates were in two languages – English, the language of the elite and Hindi (or other Indian languagea) – the language that the masses understood.

The Phalkes were also perhaps the first Indian film family. His entire family, including him, his wife Saraswati Phalke, eight children (five sons and three daughters) were all involved in the filmmaking process, with Saraswati handling some of the technical process including developing the film. His daughter, Mandakini Phalke, was in fact one of the first female actresses on the Indian screen at a time when acting in films was a much derided profession.

Dhundiraj Govind Phalke was to follow the initial success of Raja Harishchandra with other landmark films such as Lanka Dahan (1917). A prolific filmmaker, Phalke went on to make over a hundred films but died in poverty.

Of the original 3700 feet of the original film (that took 6 months and 27 days to put together) only some fragments could be preserved by the National Film Archive of India, Pune which includes portions of the first and the last reel of the film.

If a mere thousand words aren’t sufficient to quench your thirst for Phalke info, head to phalkefactory.net is a (albeit unorganised) treasure trove of information on the Father of Indian Cinema.

Recommended reading: Saga of birth of first Indian movie (Source)

Dadasaheb returned from London. A convenient and spacious place was necessary for the filming of movies. He began a search for it. By then, Laxmi Printing Art Works had shifted from Mathuradas Makanji’s Mathura Bhavan to Sankli Street at Byculla, so that his bungalow at Dadar was vacant. While in Mumbai, Dadasaheb had lived in this bungalow for seven years. He now called on Mathuradasseth, who was glad that a painstaking, imaginative artist like Dadasaheb wished to start a new venture in his bungalow. He handed it over to Dadasaheb who then shifted his family from Ismail Building at Charni Road to this bungalow. This birthplace of Indian Film Industy still stands at Dadasaheb Phalke Road, Dadar, with the name ‘Mathura Bhavan’. The subject for a movie was already under consideration. In his magazine Suvarnamala, Dadasaheb had already written a story, ‘Surabaichi Kahani’, depicting the ill effects of drinking. Before selecting the story, Dadasaheb saw the American movies screened in Mumbai such as Singomar, Protect, etc. in order to get a proper idea of the type of movies which the audiences like. He found that movies based on mystery and love were patronised by Europeans, Parsis and people in the lower strata of society. So, if a movie is to be public-oriented, its subject should be such as would appeal to the middle class people and women, so that they would see it in large numbers, and it should also highlight Indian culture.

Dadasaheb knew well that cultural and religious feelings were rooted deep in the heart. However materialistic the world may become, whatever the extent to which the outward face of religion changes due to the effects of the machine age, the common man’s faith does not languish. (This is evident even today). Dadasaheb, therefore, decided to select a story, which would be well known to people all over India. Which one then? Shrikrishna’s life or Savitri’s, the ideal married woman devoted to her husband? Or king Harishchandra’s, the sublime apostle of Truth? He started thinking constantly about it.

The machinery reached Mumbai port from London in May 1912. In the meantime, Dadasaheb had prepared a dark room and arrangements for processing the film, in his home.

Work was on for constructing a small glass studio in the compound of the bungalow. The imported machinery was brought home and was cleaned by members of the family. Dadasaheb set it up within about four days with the help of the sketch accompanying it. There were no servants. He taught Saraswatibai the rather complex and laborious work of perforating the film.

Saraswatibai worked on the film at night after finishing the household chores of the day. It took three and a half hours to perforate 200 ft. of film. (If it were to be 1,000 ft. like they use it now, it would have taken at least eighteen hours). When Saraswatibai’s arms hurt, the children would pitch in for a short while. Besides, Dadasaheb too would attend to it whenever he had time, as mentioned by Saraswatibai in the issue of the weekly Dhanurdhari dated 16th February 1946. During the day, when she was free from her work in the afternoon, Dadasaheb taught her how to develop a film. She became proficient in that too. He had also taught her to load a camera. Night and day, the whole family was engaged in this work. Now it was time to try filming. So Dadasaheb filmed the fights of the boys and the playfulness of the girls living in the building opposite. He then processed the film and made a print. He had brought a projector from Germany, which he used to screen the film on a wall. All of them were satisfied with the result.

Dadasaheb decided to use the story of ‘Raja Harishchandra’, because a play on that subject was very much popular on the Marathi and Urdu stage. He wrote the script for it and also started making sketches for stage settings, costumes etc. What about the money, however? How to go about it? The investors’ trust must be earned. Knowing that every one is fascinated by magic, he started making moves for a short film.

Dadasaheb planted some peas in a pot-and placed a camera in front of it. As transformations took place in the seeds, they were to be filmed by ‘one turn, one block’ method for which purpose, the camera was kept firmly fixed in one place where it would not be even slightly disturbed, for one and a quarter months. Actually while viewing the short film on the screen, it lasted for about one and a quarter minutes. It showed the seed growing, sprouting and changing into a climber. Dadasaheb and Saraswatibai did the developing and printing of this film together.

They were naturally eager to see how it had turned out. It was a test of the ordeals they had had to face so far. Dadasaheb had a projector, but there was no electric supply in Dadar at the time. As a result, the short film Growth of a Plant was viewed on a screen hung up in the home, using a carbide lamp. Seeing on the screen the growth of the seeds since sowing, up to the stage of the pods appearing on the creeper, the children who had gathered there clapped with joy. The Phalke couple was overjoyed now that their long and strenuous efforts were going to bear fruit. Dadasaheb mentions all this in his interview published in the issue of Kesari dated 19th August 1913.

This short film was to be viewed using electricity. Dadasaheb learnt that at Kalbadevi Mr Sethna’s shop had both electricity and a projector. He called on Mr Sethna and expressed his desire and, the latter agreed. Then a select group, was shown the Growth of a Plant. Mr Nadkarni, who had stood behind Dadasaheb, giving financial support, was, of, course, present. He was so overwhelmed seeing Dadasaheb’s magic that he was dumbstruck. He only said, “Dadasaheb, you have sowed today the seeds of an indigenous cinema industry by sowing pea”. Seeing this film, some persons offered a loan to Dadasaheb. Among them was Mr Narayanrao Devhare, a renowned photographer in the Fort area.

Dadasaheb did not, however, have anything to offer by way of security for a loan. He asked Saraswatibai for her jewellery and she too, most willingly, handed over to him all of it except the mangalsutr’a. To bring the story of Raja Harishchandra to the screen, Dadasaheb had to go through a harder test of character than Harishchandra and to depict the nobility of Taramati, he had to make his wife a beggar-maid.Thus, the question of capital was taken care of. N-ow there was no problem in advertising for artistes and other employees. So he published advertisements in Induprakash and other prominent newspapers: ‘Wanted actors, carpenters, washermen, barbers and painters. Bipeds who are drunkards, loafers or ugly should not bother to apply for actor. It would do if those who are handsome and without physical defect are dumb. Artistes must be good actors. Those who are given to immoral living or have ungainly looks or manners should not take pains to visit’. Even in spite of clear instructions, such persons came in large numbers. Dadasaheb felt so harassed that he decided to discontinue the advertisement and scout for the artists himself.

One Pandurang Gadadhar Sane, doing female roles in a theatre company named ‘Natyakala’ in Mumbai and another Gajanan Wasudev Sane, doing roles in Urdu plays, joined Dadasaheb’s Phalke Film Company on a salary of Rs 40 per month. One Mr Dattatray Damodar alias Dadasaheb Dabke, an acquaintance of Gajanan Wasudev Sane, had a good physique and an imposing personality. Shri Phalke took him in his company and gave him the role of Raja Harishchandra. For the role of Rohidas, however, he could not get a boy because he too would have to go with Harishchandra and Taramati to live in forests, away from society. To complicate the matter further, Rohidas was to die in this movie. Whoever was approached for his son to do the role said that it was impossible for him to see his son’s distress and ultimate death in the movie. At last Dadasaheb decided to assign the role to his son Bhalchandra. He was the first child actor of the Indian movie world. Now the problem was about the heroine Taramati.

In response to the advertisement, four ugly prostitutes visited him. So Dadasaheb put in bold type in the advertisements: ‘Only good-looking women should come for interview’. One day, a young woman with a passable appearance reported. She was someone’s mistress. As she was prepared to work, Dadasaheb had her do the rehearsals for four days. On the fifth day, her master came to the place of the rehearsal and shouted at her, “Are you not ashamed, acting in a movie?” and dragged her away. In his eyes, working in cinema was less honourable than her profession. Dadasaheb thumped his head in despair.

Two other women from the same profession came to stay at Dadasaheb’s house. Saraswatibai had got to look after them as her guests. Her elder brother-in-law thoroughly disapproved of it. She had, however, no other way. She did not deem it infra-dig. On top of it, the two women only ate and drank for two days and left without doing anything for Taramati’s role.

Ladies from respectable families were not prepared even to look in the direction of acting in cinema. So, throwing all embarrassment to the winds, Dadasaheb started visiting the red light areas of Grant Road, Kandewadi etc. He could not, however, find any woman who could fit in the role of Taramati. On the contrary, he had to listen to many unsavoury things from those women about working in films. One of them said that if she acted in a movie, she would be ex-communicated by her village people. Another said, “You get permission for me from my master to work in cinema”. With a couple of better-looking whores, he had a different kind of experience. They asked, “What will you pay for working in cinema?” Dadasaheb promptly replied, “1 will pay you even forty rupees a month”. They shot back contemptuously: “We earn that much in one night, many times. So what’s the use of working in cinema?” Dadasaheb kept mum. He happened to come across a girl from Goa with good features and, on asking her, she directed him to her mother who said, “You marry my daughter. Then she will work in cinema”. Dadasaheb was struck dumb.

Dadasaheb did not give up his search for Taramati, but there was no sign of finding one. Tired and dispirited, he was once having tea in Gokhale’s restaurant at Grant Road, when his eyes fell on a fair complexioned boy with smart features who was serving there as a waiter. Dadasaheb had an idea. He asked the boy about working in cinema. He was getting two meals per day and ten rupees as salary per month. On Dadasaheb’s offering to pay fifteen rupees, he promptly accepted. His name was Krishna Hari alias Anna Salunke. As in the case of drama companies, Dadasaheb’s employees had both their meals at his house and auntie (Saraswatibai) cooked for about forty people without tiring or complaining.

Dadasaheb collected the local boys as well as boys from elsewhere for acting in the movies. He also recruited those who were no .longer good enough for acting in plays, havmg lost pristine tenderness of voice. Casting was now ready. The role of Taramati was assigned to Krishna Salunke. (In some places it is stated that Pandurang Sane acted as Taramati, but there is evidence that Salunke had done the role). DD Dabke was Harishchandra, Bhalchandra was Rohidas, and Gajanan Wasudev Sane was Vishwamitra. Besides, Dattatray Kshirsagar, Dattatray Telang, Ganpat Shinde, Vishnu Hari Salunke, Nath Telang were also given important roles. The make-up of Anna Salunke posed a problem: He was not willing to shave off his moustache, as his father was alive. How could Taramati have moustache? Dadasaheb persuaded him and his father, and Krishna Hari alias Anna Salunke became the first heroine of the Indian film world.

Dadasaheb had laid down that men actors doing female roles should wear their hair long like women and take care of it. After coming to the studio they had to wear sarees and do women’s chores like sifting rice, making flour etc. The object was that they should look woman-like on the screen and not sloppy. Rehearsals were started but it was a Herculean task to get these greenhorns to act. There were many among them who had not seen a movie. It was not possible for them to know what acting meant. Dadasaheb showed them again and again how to act. An actor named Sakharam Jadhav could not make an entry like a woman; so Dadasaheb himself wore a saree and showed him repeatedly how to make an entry. When acting for such scenes, Dadasaheb had to wear a saree so often. To show the actors how to express emotions, a number of photographs from English periodicals showing expressions on different occasions were hung up at the place of the rehearsals. Exercise was compulsory for every actor. The company gave them milk to drink regularly.

Dadasaheb viewed many foreign movies,in order to study how to write a script and how to make a shooting script. He accordingly completed writing of the script of his movie. Rehearsals were also done. The shooting script was likewise ready. Now production was to begin. Dadasaheb took upon himself the responsibility for script, direction, art direction, make-up, editing and film processing. He could have done the photography too but as he was shouldering so many responsibilities single-handed, he asked his boyhood friend Triambak Balaji Telang to come to Mumbai. The evening pooja at the Triambakeshwar temple was the hereditary job of the Telang family. Although Triambak Telang was himself a hidebound conservative Brahmin, Dadasaheb had taught him still photography as a hobby. On receiving Dadasaheb’s letter, Telang entrusted the responsibility of the pooja to his brother and came to Mumbai to lend a hand in his boyhood friend’s new venture. Dadasaheb taught Telang all the mechanics of film photography and entrusted that responsibility to him. He also gave his two sons small parts in Raja Harishchandra. In short, Dadasaheb was also the progenitor of the various divisions and sub-divisions of film production.

The casting was complete. Jewellery and costumes were going to cost a goodly sum. Besides, it would have taken a lot of time to get together all the material like Raja Harishchandra’s costume, crown, wig, swords and shields, bows and arrows.. About the same time, Rajapurkar Natak Mandali (a drama company) was in Mumbai. Many of its shows were mythological. Dadasaheb already knew the proprietor of the company, Babajirao Rane. He called on Babajirao and acquainted him with his idea of indigenous movie production. Babajirao was himself a man of imagination and daring. He was impressed by Dadasaheb’s project and derring-do and, wishing to give a helping hand to this new indigenous industry, he willingly asked Dadasaheb to take whatever material he wanted. Not only that, he also asked Dadasaheb to make use of whoever from his team of actors were useful to him. As the cast was already decided upon, the latter offer could not be made use of, but much of the problem of costumes was solved by Rane. Dadasaheb thanked him profusely. Saraswatibai’s brother’s Belgaokar Natak Mandali as also Saraswati Natak Mandali offered sincere help but it was not needed. Dadasaheb, however, appreciated their support.

Dadasaheb had designed the costumes and stage scenes from the paintings of Ravi Verma and the famous artist Dhurandhar. In those days, silk sarees were available with big borders with big end-scarf. He got Taramati’s dress made of costly, high-faluting silk sarees by having some designs printed on them, which were suitable for the screen. He, however, bought the wigs for Taramati, Harishchandra and Rohidas at his own expense. He also painted the scenes of rajmahal, jungle, mountains, fields, caves etc. himself on curtains.

After the rainy season, the work of erecting sets started in the compound of the bungalow. Painter Rangnekar was appointed on Rs 60 per month. In the meantime, it was decided to do some out-door shooting at Wangani, a village on Mumbai-Pune railway line. A funny incident took place on the first day. An actor, who was to do a female role, was not willing to remove his moustache while his father was alive. Dadasaheb had to entreat him as in the case of Krishna Salunke and thereafter all the actors and workers left for Wangani.

Seeing the troupe of people wielding swords, shields, spears and wearing unusual clothes, a whispering campaign was afoot in the village. Some frightened villagers informed the village Patil, ‘Some armed dacoits have entered our village’. The Patil was also shocked and immediately reported the matter to the Fouzdar who arrived in a short time with a police party and left for the temple where the troupe had lodged. Those persons pleaded imploringly,

‘Sir, we are not dacoits. We work in cinema and have come here for shooting’. When, however, no one in this country knew what film shooting was, had never seen one, how would the Wanganikars know it? The Fouzdar did not believe their story, arrested them and took them to the police station.Presently, completing some urgent tasks in Mumbai, Dadasaheb reached Wangani. He came to know what had happened. Promptly calling on the Patil and the Fouzdar, he explained to them what cinema was, what was meant by its shooting and took them with him to show them a demonstration of film shooting. Without loading the camera with a film, he went through the motions of filming a scene in. which Raja Harishchandra wields a sword to behead Taramati who had been sentenced to death. God Shankar appears and: stops Harishchandra. Viewing the scene and getting an idea of Dadasaheb’s new venture, the Fouzdar and the Patil apologised to him and released the arrested persons. The shooting then started without any hitch.

A heart-warming incident took place during the shooting at Wangani. When Bhalchandra, in the role of Rohidas, was playing with the children of Rishis, he fell on a rock and started bleeding from the head. Dadasaheb always carried a first-aid box with him. On being treated, the bleeding stopped a good deal, but Bhalchandra was still unconscious. Some persons suggested that he should be taken to Mumbai for treatment and, after he had completely recovered, the shooting could be resumed. However, a scene was to be filmed in which Rohidas is dead and his body is carried and placed on the funeral pyre. As Bhalchandra was unconscious, he would not make any movement as wanted for the scene. Besides, waiting until Bhalchandra was well enough for the shooting and reconstructing the whole scene, would have meant time and money. In order, therefore, to avoid both, Dadasaheb stoically got the scene filmed in that difficult situation. After it was over, however, he broke down. When he saw the scene on the screen, his handkerchief was drenched with tears.

It was financially impossible to go to Kashi and shoot some scenes there, however much Dadasaheb would have loved it. The episodes happening in Kashi were quite a few. Ultimately, they had to be filmed at Triambakeshwar. The unit camped at Triambakeshwar for about a month. It was a family of about fifty people, comprising artistes, technicians and other staff. All of them lived in a building near the studio. At the time of outdoor shooting, meals were sent from Dadasaheb’s home. Auntie (Saraswatibai) did all this work with care and consideration. Telang’s wife helped her.

Dadasaheb did not okay a shot unless he was completely satisfied, notwithstanding how much the photographer and others admired it. He did not mind the amount of time and money it cost. He was, of course, exceedingly eager and anxious to confirm that the shooting done was all right. Even for outdoor shooting he would make arrangements in advance for developing the film. He would develop at night some of the film shot during the day and if it were not to his liking, he would shoot it again the next day. He was thus so engrossed in his work at night that he not only did not get enough sleep but also could not often take time off for his evening meal. He did not get time even to read the daily newspaper. As he worked very meticulously, it took 6 months and 27 days to produce Raja Harishchandra, a film of 3,700 ft., a mere four reels. As a result, the expenditure too went up.

Confronting numerous difficulties, Dadasaheb completed the first Indian movie. In earlier days, a play started with an introductory episode. Somebody floated the idea that this movie should also have such a beginning. Everyone suggested that Dadasaheb should be the compere and auntie should be the Nati. She did not, however, agree. Dadasaheb tried to persuade her: “Why do you object to standing by my side? Your two children will be with us and the cameraman is our Telang. Why should you then refuse?” Auntie said, “I will help you in all ways from outside. I won’t mind working even as a coolie, but 1 would not like to appear on the screen”. Others too urged her, but she did not budge. At last, Pandurang Sane did the role of Nati and filming of this episode was also over. Dadasaheb then began his efforts to get the film screened. All this information is from an article containing Saraswatibai’s memoirs.

Saraswatibai stated in an article in the May 1962 issue of the magazine Shreeyut: “He pledged all his family, all his life to make the cinema industry indigenous”.

I see you share interesting content here, you can earn some additional cash, your website has big

potential, for the monetizing method, just search in google – K2 advices how to monetize a website